Well, I said I was going to try and keep some of my interests that aren't directly related to the stated purpose of the blog a little more on the down-low, and paleontology in particular, I was planning on making a once a Monday thing. But, I don't really have any gaming related topic to cover right now, or science fiction or fantasy either. I've honestly been too busy to give much thought to those things, and I've been caught up in a lot of personal issues (not bad ones, just busy ones) and a lot of stuff at work too that has kept me even busier. My mind has not been free to wander in the realms of imagination with as much lack of constraint as I'd like. So, I'm going to punt and do something related to dinosaurs again, just because... well, at least I've had that on my mind, so I can pull something up without straining anything.

What are the biggest dinos? More specifically, what are some of the really tantalizing dinos about which we know every little, but which might be staggeringly bigger than the specimens about which we know more? If that makes any sense. Let me make a small list:

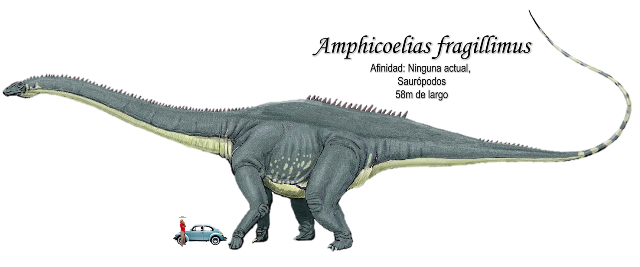

Amphicoelias fragilimus This has got to be one of the most notorious dubious giant dinos. Named by Cope himself, there were two specimens and two species named; A. altus and A. fragilimus. The prior has seniority, although the paper was not very diagnostic, and at least a few specialists presume that it actually refers to merely a specimen of Diplodocus. If so, it would actually make Amphicoelias the senior synonym, but because the paper isn't very diagnostic and there's not much agreement around the merging of the two names, there's very little risk that that will actually happen. (The best, most recent cladogram that I could find shows it within Diplodocidae but outside Apatosaurinae and Diplodocinae.) It's the second specimen that really is interesting, though. The bones were illustrated and described, but as the name suggests, they have not survived. In fact, nobody knows exactly what happened to them, although the prevailing presumption is that they were too fragile to last, and the fragments were eventually discarded after the fell apart too much to be useful. The interesting thing about them, of course, is the enormous size attributed to them. So enormous, that many people believe that Cope may have introduced some kind of typo in describing them, because they doubt that they could truly be that large.

There have been a lot of attempts to estimate the real size of the animal assuming that Cope was right. This is difficult, because all that we have is a partial vertebrae, which of course doesn't survive. Attempting to scale this to other parts of the body and estimate the total size of the animal has given length estimates between 160 and 240 feet long; compared to about 90 for Diplodocus. As other extremely large dinosaurs have gradually appeared over the years (Argentinasaurus, Puertasaurus, Dreadnaughtus, Patagotitan, etc.) this doesn't sound as crazy as it used to when Diplodocus was the longest dinosaur that we knew of and Brachiosaurus the most massive. But it's still significantly larger. Or at least, longer—keep in mind that Amphicoelias is believed to be a relatively slender animal.

"Brachiosaurus" nougaredi Found in North Africa, this animal was believed to be a separate species of Brachiosaurus and the age of the rocks was believed to be late Jurassic... partly because of the proposed presence of Brachiosaurus. However, they are extremely fragmentary remains, and the supposed positioning of them in the dinosaur family tree has been pretty much debunked—in fact, the remains aren't even believed to come from the same species at all; it is now believed that the majority of the remains represent some kind of titanosaur, and the age of the rocks is believed to be Albian. Either way, the sacrum (a portion of which is all that we have) is as big as any sauropod sacrum ever seen, including Argentinasaurus, so this is a big animal. Whatever exactly it is. Given the age, maybe it's a Paralititan, although if so, it's on the complete other side of the African continent.

Breviparopus This is actually a fossil trackway not skeleton (or portion thereof) so it's a whole different kind of classification. While in general, its difficult to classify what kind of animal made a trackway, there's actually fairly good evidence that this was a brachiosaur (narrow -gauge stance, thumb claw as part of the print.) If it was, it was the biggest brachiosaur and among the biggest sauropods. Either way, it's a bit iffy based not only on the nature of the evidence, which is circumstantial by definition, and also based on the chronology. Traditionally dated to the Middle Jurassic (quite a bit earlier than either Brachiosaurus or Giraffatitan) but there is evidence to suggest that it may come from the Aptian instead (quite a bit later than Brachiosaurus or Giraffatitan but not later than late appearing brachiosaurs like the three Cedar Mountain brachiosaurs. Keep in mind that Sauroposeidon is no longer believed to be a brachiosaur, but rather a a close and more advanced relative in Somphospondyli.) Given its time, it may be an African relative of Sauroposeidon, although how exactly an relative of Sauroposeidon got to Africa is not explained—it's obviously statistically impossible to suggest that both Brachiosaurus and Giraffatitan had derived ancestors that were part of the same derived family unless they came from a single source. Possibly there was some kind of land bridge of sorts that still connected Western North America to Eastern Africa in the early Cretaceous? I don't know of anyone proposing such a thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment