The classic tyrannosaur lineage is more geographically constrained that the broader tyrant lineage; we've only got representatives from Laramidia—the northern half at least of such, and a few spots in Asia. As we've already seen, Appalachia seems to have had somewhat distant cousins like Dryptosaurus as apex predators, and in the former Gondwanan continents of the south, abelisaurs—descendants of Ceratosaurus—and maybe some lingering carnosaurs—cousins of Allosaurus—were the top predators.

Classic tyrannosaurs were also big, of course. In fact, inordinate amounts of ink have been spent on discussing the size of them, relative to other large dinosaurian carnivores. This is all fairly silly, as our sample size is too small for any of these animals to make a definitive discussion of their size—assuming we even have complete enough remains to make a meaningful comparison in the first place, which is also often not true. But clearly T. rex was among the largest dinosaurian carnivores, and in some ways, perhaps the most frightening. Relative to a big predator like Giganotosaurus or Spinosaurus, a big tyrant was likely faster, had a much stronger bite, may have hunted in packs or groups, had better vision, had a better sense of smell, etc. It's no wonder that they continue to reign at the top of the "charismatic big scary dinosaur" chart, even as some other animals might measure a tiny bit longer, or whatever.

Daspletosaurus torosus. First assumed many, many years ago to be a new species of Gorgosaurus, Daspletosaurus wasn't really formally described and named until 1970; many decades after its discovery. It's interesting, though, that it coexisted with Gorgosaurus as near as we can tell, at least at the younger end of its range, and maybe Albertosaurus after that. There aren't many specimens of Daspletosaurus; only two, actually of the first named species, although several other specimens that await formal description and may represent additional species have also been recovered and talked about informally for years (the so-called "Dinosaur Park tyrannosaur" and the "Two Medicine tyrannosaur." The actual type species are from the Oldman Formation rather than the Dinosaur Park or Two Medicine Formations.) This gives Daspletosaurus a fairly wide temporal range; 77-74 million years or so ago, smack dab in the middle of the "Judithian faunal assemblage" of which it was the apparent king. Although not particularly large; only about 30 feet or so long, Daspletosaurus is much more heavily built and robust than his albertosaurine contemporaries.

Daspletosaurus remains have been found in a small group (three individuals from the more recent Two Medicine bunch) along with some hadrosaur remains, which suggest some kind of group socialization. Bite marks interpreted as the result of fighting with another daspletosaur have also been recovered from the face of another. This may or may not indicate packing behavior, but it is intriguing. More interesting are the attempts to explain how Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus avoided direct head to head competition. Although, again, our sample size is too small to tell us much with confidence, it's assumed that Daspletosaurus was less common than Gorgosaurus, and certainly it's heavier and more robust. Suggestions that it specialized in ceratopsians seem doomed to failure, as we have more evidence of Daspletosaurus feeding on hadrosaurs than horned dinosaurs. There doesn't seem to be any correlation with regards to elevation or distance from the interior seaway either, which would imply an ecological separation of some kind; although it's possible that Daspletosaurus was more common in the south and Gorgosaurus more common in the north. Thomas Holtz has suggested that there may have been an ecological preference that lumped classic tyrannosaurs with chasmosaurines and hadrosaurines, while the albertosaurines were lumped in a different ecotone with the centrosaurines and lambeosaurines. As the environment changed and the seaways retreated the latter group seems to have gone extinct (or at least become very, very rare in the case of lambeosaurines) while the former prospered. This may suggest a preference for the slightly more dry, inland plains and whatnot as opposed to coastal forests, but again, that's a suggestion that isn't really backed up by much data yet.

For a variety of obvious reasons, Daspletosaurus has often been proposed as a direct ancestor of T. rex, but that, of course, was more common before more variety in classic tyrannosaurs was uncovered. Many cladograms now show Daspletosaurus more closely related to the Asian taxa than to T. rex itself, suggesting either that there was coming and going across a Bering land bridge or that the situation is simply more complicated than previously assumed.

Teratophoneus curriei. Utah's Kaiparowits Formation, from the slightly later Campanian (76-74 million years ago) is pretty recently described and this entire new southern expansion of Laramidian fauna is all pretty new and still somewhat poorly known. The environment has been interpreted as a coastal "jungle" and is interesting for its proliferation of new species—which, granted, are similar to species further north, but not too similar. Known from only a single partial skeleton with a few other bits referred to it since, which is not fully grown, the specimen we have is about the same size Daspletosaurus—about 20 feet long, but has a rather more deep and stronger head. The Hone and Loewen cladograms have Teratophoneus as intermediate between Daspletosaurus and Tyrannosaurus but the Brusatte and Carr cladogram has it as more basal yet with Daspletosaurus as a fairly derived taxon.

The fauna in which Teratophoneus hunted seems to be extraordinarily rich, if only recently described in many cases. Saurolophonine and lambeosaurine hadrosaurs are known (Gryposaurus and a different species of Parasaurolophus respectively) and both chasmosaurine (Kosmoceratops, Utahceratops) and centrosaurine (Nasutoceratops) are known, an extraordinarily diverse assemblage, and avisaurs, caenognathids, ornithomimosaurs and troodonts are also known. The formation is still the new guy on the block, and presumably many more finds are yet to come forth from it.

The interesting thing that has been proposed is that there may have been a northern and southern dispersion of species that was separated from each other, and that Teratophoneus (and Lythronax) represented a southern radiation that was independent of what was happening further north in Laramidia and in Asia. The Brusatte and Carr analysis suggests, on the other hand, that all of these regions are substantially intermingled and there is little evidence for geographic constraint between them. Whatever the case may be, the southern portion of Laramidia clearly needs more exploration; there may have been quite a bit more interesting things going on here than we realized.

Bistahieversor sealeyi. This guy has one of the most difficult names for me to say and type, for whatever reason. Known unofficially as the "Bisti Beast" which on the other hand I really like, it was found in New Mexico's Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, famous otherwise for it's weird hoodoos and weird Navajo name. This is part of the Kirtland formation from 74 million years ago, making the Bisti beast contemporaneous with the others discussed so far today. The Kirtland Formation is another one that isn't quite as well known as some others and for whatever reason fossils referred to it have bounced in and out of the Kirtland and the underlying Fruitland and overlying Ojo Alamo formations, meaning that it's a little difficult to get your arms around what's actually in and out. It seems to have the usual suspects, though—large chasmosaurines like Pentaceratops and Titanoceratops, ankylosaurines, hadrosaurs like Kritosaurus and Parasaurolophus, often with different species than known from elsewhere (like further north), troodontids, etc. A lot of material has been referred to various tyrannosaurs; albertosaur, daspletosaur, and Aublysodon, a taxon which is now considered dead in the water, but mostly these have now been subsequently referred to Bistahieversor. The Hone and Loewen cladograms suggest that this is a derived classic tyrannosaur, but Brusatte and Carr claim that the analysis over-samples snout height and that the animal should actually be seen as a Dryptosaurus grade tyrannosauroid outside of the classic tyrannosaurs altogether; although if so, one that curiously mimics some of their features, at least superficially. Either way, it has some somewhat strange details of its skull construction, including a mysterious hole above its eye socket, a lower jaw keel, and a skull stabilizing joint, or "locking mechanism" on its forehead.

Lythronax argestes. As we move along the Hone or Loewen cladogram, this fella comes next. Lythronax is from the Wahweap Formation; an earlier part of the Grand Staircase/Escalante National Monument in southern Utah, underlying the formation in which Teratophoneus was found. The Wahweap formation isn't as well known, but it has the earliest known centrosaurine Diabloceratops and hadrosaurs closely related to Maiasaura and a poorly known lambeosaurine, some poorly known (and unnamed) pachycephalosaurs and ankylosaurs. Known from relatively fragmentary skeletal remains itself, the big story about Lythronax is its age; from earlier in the Campanian, at 80 million years ago, Lythronax is the earliest known of the true tyrannosaurids. The western seaway was also at its greatest extent during this time, which has prompted the idea that the southern part of Laramidia may have been effectively cut off from the north, thus prompting the radiation of true, classic tyrannosaurs right here in the American southwest.

Lythronax, in spite of its temporal placement, isn't particularly primitive, however. It's closest on the phylogenies to Daspletosaurus and the rest of the big, classic tyrannosaur clade. Many features of its skull in particular are very similar to what appeared a lot later, and it was a big surprise to see them show up as early in the stratigraphy as it did. Of course, Daspletosaurus comes in relatively primitive on the Hone and Loewen cladograms, but much more derived on the Brusatte and Carr diagrams. Either way, there's still a fair bit of work with regards to "ghost lineages" that explain how we get from gracile and relatively small tyrannosauroids like Eotyrannus and Xiongguanlong to the bigger tyrannosaurine grade animals that appear later. We don't know where they came from or what intermediate steps may have gotten them from one grade to the next, or what kind of diversification they underwent during the earlier Campanian and before that lead to the classic forms.

Lythronax was a fairly big animal; bigger than Teratophoneus (although remember that the specimen for the latter was not a fully grown adult) and pretty close to Allosaurus sized.

Nanuqsaurus hoglundi. On the other hand, it's not just the southern part of the range where exciting new tyrant finds are popping up. The Prince Creek Formation in Alaska, north of the Brooks Range and the Arctic Circle is turning out to be an interesting dinosaur-bearing formation, from about 69 million years ago in the early Maastrichtian. Different cladograms give different positions for Nanuqsaurus, but it is clearly a fully derived tyrannosaurine animal, although only half the size (or even less) of T. rex at about 20 feet long; explained away as likely a result of less plentiful prey due to the relatively harsh conditions in which it lived. Keep in mind that during the Mesozoic, the whole earth was warmer than it is now, and there was no permanent ice cap at either pole, but that doesn't mean that the Arctic winters weren't still cold, most likely frozen, and packaged with long periods of no sun.

Not a lot of the animal is known; just some fragments of the skull, really, but they've proven to be pretty diagnostic. Nanuqsaurus is also a fully grown animal as far as we know. It shared its habitat with troodonts and dromaeosaurs, a unique pachycephalosaur, the youngest known species of Pachyrhinosaurus (a relic taxon, really) and some Edmontosaurus-like hadrosaurs and other, smaller ornithopods like Parksosaurus or Thescelosaurus. Some of these may have been migrants that came during the summer and went back further south during the winter (Parksosaurus is known from Edmontonian assemblages further south, for instance) and it would have been close to whatever putative land bridge popped up from time to time between Laramidia and Asia—although sea levels were generally quite high.

Zhuchengtyrannus magnus. I'm going to make another slight diversion from the Hone cladogram in favor of the newer Brusatte and Carr cladogram, partly because I think it makes the most sense to cap off a discussion of the tyrant dinosaurs with T. rex itself. So I'll talk about its two closest relatives first; Zhuchengtyrannus and Tarbosaurus. Both are from Asia, although not particularly close to each other. The dating of the Chinese Zhuchengtyrannus is a little spotty; it might have been late Campanian or early Maastrichtian; contemporary with later specimens of Daspletosaurus in North America. Although known only from parts of the skull and jawbone, it's enough to show that "ZT" as he's affectionately called by his describers, was a very large animal; not as big as the biggest T. rexes (i.e. "Sue") but as big as many of the rest of them, and bigger than most specimens of Tarbosaurus. Given the sample size; again, it's right there in the same range as T. rex in terms of size and morphology both, although it has a number of quite unique features to its skull.

Its environment isn't very well known either; it was a floodplain during the Cretaceous, and had a relatively primitive centrosaurine (the only one known from Asia), smaller often bipedal leptoceratopsids, the enormous hadrosaur Shangtungosaurus and some ankylosaurs. It's interesting to see the differences between the Asian and Laramidian faunas; this would have been a contemporary with the Edmontonian faunal assemblages of North America.

It's possible, due to the closer relationship between them, that T. rex evolved among these Asian tyrants and then migrated to Laramidia, rather than evolving in situ from Daspletosaurus. Of course, it could have gone the other way as well. It's hard to tell as there's a bit of a gap in North America in some regions, and exactly where each individual classic big tyrant came from and how it dispersed between the two continents is a bit mysterious still. It certainly seems that there may well have been multiple crossings in the Bering region, separated by local development and then dispersal. This may well have happened between the northern and southern regions of Laramidia over time as well, giving us three potential "cradles" of the big, classic tyrants.

Tarbosaurus bataar. This is an extremely well-known tyrannosaur from Mongolia's Nemegt Formation. Although this formation hasn't been absolutely dated, it's almost certainly from the early Maastrichtian, maybe 70 million years or so ago, so a little bit earlier than T. rex itself, and more temporally contiguous with the Two Medicine Formation and the Edmontonian fauna of North America. Tarbosaurus was long known as the animal most similar and closely related to T. rex. but it does have some notable differences. It's a bit smaller and more slender, for instance. This is especially noticeable in the skull, which is really quite narrow and lacks the extended "swelling" seen in T. rex which gave it its famously binocular vision. It also has a jaw-locking mechanism which is still often called "unique" although it isn't anymore; there was quite a stir when Bistahieversor had the same feature. And it has more teeth than T. rex. While some of these features seem more primitive than the direction T. rex itself was going, on the other hand, Tarbosaurus has the most reduced forearms of any tyrannosaur.

When Tarbosaurus was first described by Soviet paleontologists, it was proposed to have been found with a number of other smaller tyrants: two species of Gorgosaurus, a species of Tyrannosaurus (the ultimate source of bataar actually), and possibly more. Later researchers collapsed most of these into growth stages of Tarbosaurus but created Maleevosaurus, a species of Albertosaurus, "Shanshanosaurus", Jenghizkhan, and a number of "teeth species." All of these have pretty much been collapsed into growth stages of Tarbosaurus now except for Alioramus which is recognized as a genuinely unique and different animal. This spread, once the conspecific origin of all of them was recognized, gives us a good deal of understanding of the growth of the animal, the only other tyrant for which this is known well is probably T. rex itself.

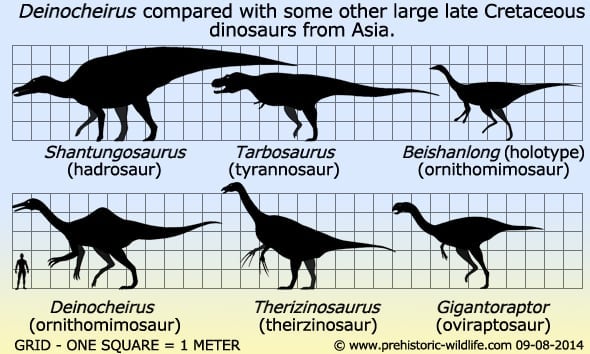

As with most other dinosaur faunal assemblages, the Nemegt represents a floodplain that was mostly fairly wet, but which did experience either seasonal or at least occasional droughts. It's famous for its wide diversity of oviraptors and other paravians, lots of ornithomimosaurs, including the enormous and very odd Deinocheirus which was probably an attractive prey animal to Tarbosaurus, as well as more typical fleet-footed ornithomimsaurs like Gallimimus that were probably too fast to be a ready source of food. Gigantic Therizinosaurus was also there, but there were also big titanosaurs (possibly two, but probably just one, Nemegtosaurus. It's known only from a skull, while a second titanosaur is known only from post-cranial skeletal material.) There are several ankylosaurs and more than one pachycephalosaur, and the large hadrosaur Saurolophus, one of the few genera that actually is present on both Laramidia and Asia.

As with most other dinosaur faunal assemblages, the Nemegt represents a floodplain that was mostly fairly wet, but which did experience either seasonal or at least occasional droughts. It's famous for its wide diversity of oviraptors and other paravians, lots of ornithomimosaurs, including the enormous and very odd Deinocheirus which was probably an attractive prey animal to Tarbosaurus, as well as more typical fleet-footed ornithomimsaurs like Gallimimus that were probably too fast to be a ready source of food. Gigantic Therizinosaurus was also there, but there were also big titanosaurs (possibly two, but probably just one, Nemegtosaurus. It's known only from a skull, while a second titanosaur is known only from post-cranial skeletal material.) There are several ankylosaurs and more than one pachycephalosaur, and the large hadrosaur Saurolophus, one of the few genera that actually is present on both Laramidia and Asia.Tarbosaurus also appears to be present in the Subashi Formation, although it was first classified as the rather dubious "Shanshanosaurus." The age of this formation is dubious, but it seems to have been similar to the Nemegt; maybe a little bit younger, with a big hadrosaur and big titanosaur also present.

Tyrannosaurus rex. Booyah! We finally get here. Did the big daddy evolve in America via anagenesis from Daspletosaurus and the two Asian taxa came from northern Laramidia, or did it evolve in Asia from Zhuchengtyrannus or Tarbosaurus and spread across North America? Either way, T. rex is the epitome of tyrant evolution; the most robust, the largest specimens, the strongest, most reinforced skull, the widest extension of the skull base, giving it the best binocular vision, etc. Although we have better sampling of T. rex than most tyrannosaurs, we still don't really know much about its maximum size or how it compared to other large predatory dinosaurs, but "Sue" is an impressive specimen (which you can see in person at the Field Museum in Chicago, if you're ever out that way).

T. rex has been the subject of a lot of weird ideas over the years. Some recent controversies include the "predator vs. scavenger" debate, which is considered pretty conclusively "solved" to the degree that an obligate scavenger of T. rexes size makes little sense (plus partially healed tooth marks from the animal are found in many prey species, representing predation attempts that failed.) The speed of T. rex was the subject of a lot of debate. It's true that T. rex had among the longest hind limbs relative to body size of any therapod, but given its size, it probably didn't "gallop" all that fast. It probably could walk like nobody's business, with a huge stride length, though. It was certainly fast enough to deal with its prey. There may be two morphs; a gracile and robust, which may represent sexual dimorphism, but this is controversial. Regardless, there are a lot of growth stages known, with a number of juvenile and sub-adult specimens known from at least partial remains, but often from fairly good remains. Younger T. rexes had features that could almost be considered "primitive" to the group; more gracile proportions, longer snouts, and less pronounced swelling of the back of the skull. T. rex appears to have "plateaued" at sub-adult stage for some time and then grew very rapidly into full adult status. This suggests that T. rex's dominance of the ecosystem may have been so total that it not only was the apex predator as an adult, but also filled other predatory niches as subadults; i.e., in the role of both lions and leopards and hyenas all at once, depending on age set. One notable controversy here is the legitimacy of the genus Nanotyrannus. While some still defend it, it's mostly seen as a juvenile T. rex.

There is some evidence for cannibalism and pack hunting, but because the interpretation of the evidence is subject to a great deal of debate, this has been controversial.

T. rex is the charismatic face of the Lancian fauna, the final, last faunal assemblage associated with the dinosaurs, from 68 or so to 65 million years ago, at which point the K/T Extinction event occurred. The Lancian fauna is named for the Lance formation of Wyoming, but the Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota and Montana is from the same age, as well as the Scollard and Frenchman Formations of southern Alberta and even the Ojo Alamo formation of New Mexico overlaps the earlier side of this range, and T. rex has been found in all of them (technically, the remains in Ojo Alamo are "indeterminate tyrannosaur" but they most likely are referable to T. rex.) In the transition from Edmontonian to Lancian, it is believed that the western interior seaway retreated significantly and ecological conditions changed across Laramidia. Fauna that was more associated with the inland plains spread, while fauna associated with the prior coastal floodplains faded, or went extinct completely. The albertosaurs were gone, the lambeosaurines were gone (with maybe an exception or two here and there), the centrosaurines were gone. In fact, the Lancian is notable for it's relative lack of diversity. While Bob Bakker's methods have drawn some criticism, it's still notable that he pointed out that Triceratops makes up over 80% of the fauna from Hell Creek, Lance, Scollard, etc. while Edmontosaurus, a relic from the Edmontonian, makes up most of the rest of it. In the south, Alamosaurus and Quetzalcoatlus are notable additions, while T. rex is the only major large predator. Some smaller animals, like leptoceratopsids, maybe from Asia, or maybe they were just in the upland regions that resisted fossilization in earlier faunal assemblages, seem to reappear, and late-breaking hypsilophodonts like Thescelosaurus are still hanging around. There are small predators and/or omnivores like troodontids and ornithomimosaurs still, and a few ankylosaurs are known too, etc. While the southern part of Lancian Laramidia was described by T. M. Lehman the book Mesozoic Vertebrate Life as "the abrupt reemergence of a fauna with a superficially 'Jurassic' aspect" it's probably more fair to compare it to the Nemegt in Asia in most respects. By "superficially Jurassic" he means a big sauropod was the most prominent herbivore, which the Nemegt already had with a very close relative of Alamosaurus. That isn't really fair, because there were southern ceratopsians too, like Bravoceratops and Ojoceratops, both closely related to Triceratops and maybe even one of them is ancestral to it. While the story of "pockets" of isolated ecosystems during the Judithian and even Edmontonian being the reason for the incredible diversity across a relatively small area that was later wiped out by transgression of new species which spread over the whole area and gave Laramidia more of a same-ness across most of the continent as the pockets were later linked as sea levels fell is interesting, it's also been criticized by some, and may not have been what was really going on at all. Bob Bakker, in fact, used the same data, or at least some of it, to propose that something was going seriously wrong with the dinosaur population right before the extinction because of this lack of diversity, and so he dismisses the idea that the comet impact was the culprit (although he doesn't dismiss that it did at least happen.)

|

| Alamosaurus, T. rex and Quetzalcoatlus |

I doubt that. I think the extinction would have happened whether we had a diverse population like the Judithian or the more "samey" population that we did have of the Lancian. The real curious question to me is the what if: what if Tyrannosaurus rex wasn't the apex of tyrannosaurian evolution? What would have come next and from what quarter? We'll never know, of course, but that's a fun line of thought to pursue.

No comments:

Post a Comment